Developing Strong Product Judgment

How great product managers make hundreds of smarter decisions each year

I was working with a product manager last week to generate a welcome-email experience for a new product, and, I’ll be honest—the first draft was uninspiring. I gave the PM direct feedback about each message, but I couldn’t shake the idea that maybe there was a better way to upskill the PM. I decided that what I needed to teach wasn’t how to address my concerns, but rather how to teach good product judgment. Before we dive in, I’d like to distinguish product judgment from product sense. To me, product sense is the ability to choose the right problems and the right solutions to those problems so that products can grow faster with fewer failed experiments. Meanwhile, product judgment is how we make the hundreds of smaller decisions we are required to consider when crafting something of true value to the market. Whereas the former might include questions like “Should we build a chatbot?,” the latter speaks more toward one level down: “What pre-seeded questions should we show the user to get them using that chatbot?” In the case of the welcome-email journey, the feature set for MVP launch is well settled, and it’s now time to figure out what we should say about them to onboard and excite the user. While I’m focusing on email journey content in this post, the model I’m about to share is one I use in nearly all smaller product decisions regardless of style or impact.

Draw from Experience

What do we know from our own experiences already about the problem at hand? This sounds so simple and obvious, yet we often jump straight in and forget to first reflect on what we’ve already learned. In our last product launches, for example, what sorts of welcome emails had high open rates and/or high click-through rates? Which ones did not? Our own personal experiences are far from comprehensive, but typically we already know something about what works and what doesn’t from what the market has taught us, and this should be the first reservoir of knowledge. This guidance can also be construed to mean “check your metrics,” and reflect on what we already know about our users and their needs that might inform how we tackle the problem at hand.

The voice in my head reacted as follows for this specific challenge:

Keep the messages very short

Focus on one or maybe two topics at most per message

Try to make it personal

Spend real time making the first sentence strong

Include a graphic or animated GIF to clarify how to create value

Research What’s Out There

Most products need to be novel in only about 10% to 20% of what they do to be massively successful. For example, if your product is a new AI-driven chatbot, then its core value isn’t about innovating on payments. In this case, you don’t need to break new ground on how payments are implemented. In fact, it will increase cognitive load on your users to change patterns where you’re not trying to get noticed. With this example, when it comes time to implement payments, spending a few hours researching how the best companies handle payments and modeling your product’s experience off theirs is entirely sufficient. The mistake I see, however, is trying to divine how payments ought to work based entirely on real-time opinions and feelings. This takes precious time away from the critical and novel 10% to 20%. Frequently the best products have already run dozens of A/B tests, conducted thousands of hours of user experience tests, and hired some of the best product people and designers on the planet to get these answers.

If the work we need to do isn’t part of breaking new ground, research and find inspiration from what’s already working well in the market and adapt it to your own needs. In my onboarding email sequence example, this would mean signing up for 10 popular and well-regarded products and analyzing in great detail how they each perform onboarding, and then assessing which aspects are worth copying for your product. How long is each message? What do they emphasize? How long do we get between messages? Do they use images or links to videos? Is it from the CEO or someone else? And so on…

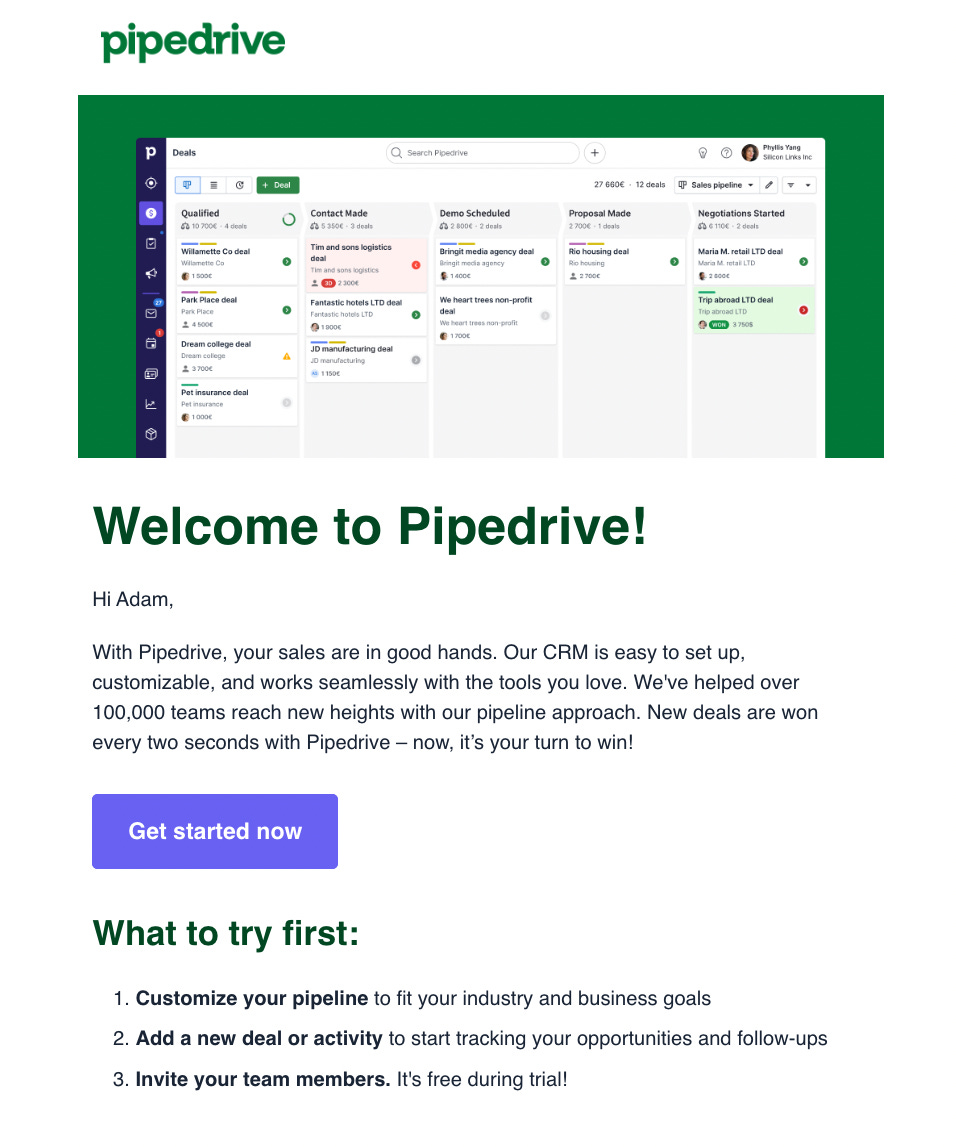

Let’s look briefly at the first two emails Pipedrive sends as examples:

Here’s my internal monologue when I review the above examples:

Very light on text

Clear CTA to get into the app

Reminds user of value proposition at a high level

Gives concrete suggestions for how to start

Not very personal, and how do I get help?

Repetitive use of “Welcome to Pipedrive” in subject and first line of message

Second message comes one day after first

Second message focuses directly on training

I would take this process through the first few weeks of content across at least 5 to 10 well-run, well-loved company flows and compile all my notes before writing much myself.

Consider the First Principles

If you take only the first two steps above, you’ll get a decent outcome, but not one that perfectly fits your product. It will be polished and reasonable, but it will be mimetic and might not be great. The final big element to add to the puzzle is to consider the first principles that undergird the challenge at hand. First principles are the underlying assumptions beneath our challenge. In our example, this would sound like asking ourselves:

What is the purpose of a welcome email in the first place?

Do people even read welcome emails?

What should every welcome email contain in terms of content?

What knowledge would users of our product need to have on Day 1 to be successful?

Is a welcome email the best mechanism for reaching our customers when they sign up? Why or why not?

These first-principles questions will guide us toward product-specific thinking that will dramatically improve our chances of making the right first decision, tailored to our specific circumstances.

The People Matter Too

Finally, we need to think about the people who have to love what we’re doing for it to be accepted and who have intelligent opinions. For the lucky few of us building in small enough companies that can focus only on the customer, fantastic, but for all the rest, our work products won’t make it out the door even if we do all the previously recommended steps but forget to consider the people who need to approve of the work. This might be the CEO, the VP of Product, someone in sales, an external consultant, or a whiny member of the team who gets a lot of respect because they are often right. It doesn’t matter who; what matters is that we spend some time thinking about their interests, the intelligent critiques they might make, and what they expect. Frequently these outside views give us tremendous signal about what we’re missing from our vantage point. Even if we don’t change our judgments based on how we expect them to react, we will at least be armed to explain why we did not and to have considered their interests. As organizations get larger, these groups of “stakeholders” get larger and more cumbersome to corral, so I’m not suggesting that we water down our judgments to the lowest common denominator. However, if we know, for example, that the CEO likes or hates a certain turn of a phrase or cares deeply about a particular value proposition, we would be wise to consider it from the start.

In this case, I knew the CEO would be thinking about:

Making the user aware of the product’s free trial option

Giving them an example to use in the context of the free trial to build trust

Summary Thoughts

In summary, developing strong product judgment is an essential skill for product managers who aim to make informed decisions that grow their products. It’s a process that begins with reflecting on personal experiences and analyzing metrics to draw upon past learning. Then it involves researching existing successful products to adapt proven strategies, followed by delving into first principles to ensure decisions are solving the right problems in a way that is tailored for the specific product. Lastly, it’s crucial to consider the perspectives and preferences of the reviewers within the company. By integrating these approaches—experience, research, first principles, and intelligent considerations—PMs can refine their product judgment and navigate the myriad decisions they face with confidence and strategic insight, ultimately contributing to more successful products.

Hi! If you enjoyed these insights, please subscribe, and if you are interested in tailored support for your venture, please visit our website at First Principles, where we focus on product to help the world’s most ambitious founders make a difference.