How valuable is your product, and is it worth it?

How valuable does your product need to be to justify putting your career on the line?

The best founders and product managers spend considerable time and energy assessing whether new product concepts are valuable. However, the value of products to sets of customers is not binary; each product has what I call a Success Quotient. Through spending time launching and helping many founders go from idea stage through first revenue, I am lucky to have observed certain patterns. Namely, it’s easy to see when you have a bird’s-eye view into the process that a variety of Success Quotients exist for different products deployed in different markets.

In this post I’ll establish some semi-quantitative thresholds to help you know if you should proceed or whether you need to revisit the drawing board. While this post can be applied to new product features, its main function is to describe the process of assessing early product-market fit for new products or new offerings that complement existing ones.

What is the Success Quotient?

Let’s define this new term: the Success Quotient for a new product or service is the number of people, from your target market, who have the pain your product solves, and who are immediately willing to adopt the product after being exposed to it. I like to express these as ratios because it feels strange to convert actual human beings into percentages.

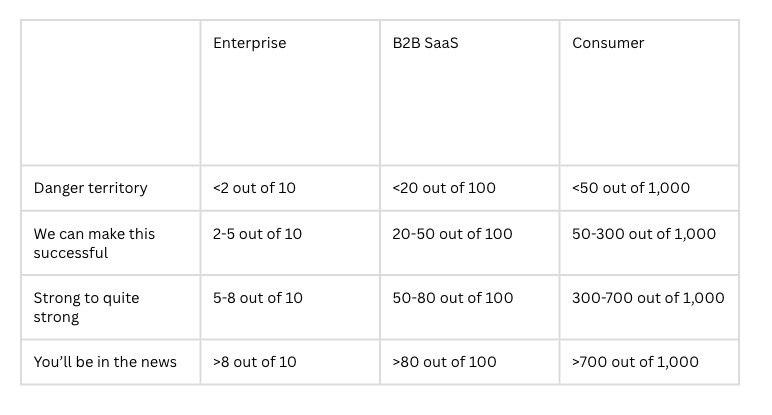

Typically I use:

X out of 10 for enterprise products

X out of 100 for B2B SaaS products

X out of 1,000 for consumer products

If a product has a Success Quotient of 45 out of 1,000, this means that if we show our product to 1,000 people who represent our target market, and they have the pain our product addresses, then 45 of them will install it, ask to try it out, subscribe on the spot, or, in the case of enterprise products, request a follow-on meeting that advances the sale.

I want to clarify that the second number in the ratio does not represent the total viewers of your Product Hunt post or recipients on your cold email list. It specifically refers to individuals experiencing the pain point your product addresses, whom you’ve engaged with directly and effectively. This engagement could be via personal emails, one-on-one conversations, or formal marketing channels. Importantly, we’re excluding those who don’t experience the described pain or who fall outside of our target markets.

Why does this number matter?

This quotient matters for two reasons. The first is that your Success Quotient gives you an idea of how big your market is, which can give you an idea of whether your price and marketing and customer acquisition costs are viable for your product. For example, if you serve a market of 5,000 specialists and have a Success Quotient of 10 out of 1,000, you can expect to max out at around 50 total paying customers. In such an example, it’s easy to see how your price point would need to be many millions or even tens of millions of dollars to justify venture-funding returns. For most products, that’s too expensive, and therefore this particular mix of product and solution are likely a bust.

The second reason it matters—and this is arguably the more important of the two—is because Success Quotients are sticky anchors. What I mean is, whatever your quotient is when you first launch your product, don’t expect it to rise massively after you raise lots more money and improve the product. You heard that right, and this is the tough-love part! It is extremely rare in my experience that a product that launches with a quotient of, say, 5 out of 100 will become a product that achieves a 50-out-of-100 ratio. You might go from 5 to 10 out of 100, or from 315 to 375 out of 1,000, but product solutions tend to anchor hard toward their initial uptake rate.

How can this be?

It’s quite simple: the Success Quotient is measuring the value of your holistic solution matched against the value of solving the pain (for more on this, see my post on quality of the solution vs. quality of the product). This is because we’re measuring the degree of excitement target users have for what we’re offering and demonstrating. They are not, at this phase, parsing the exact features, so evolutionary improvements in those features over the coming years won’t dramatically impact this particular quotient.

Sure, we’re simplifying the issues of retention, viral growth loops, and much more, but I want to keep this simple because it’s easy to delude ourselves into thinking we’re on the right track when we’ve invested so much of ourselves to get to launch in the first place. For now, these other considerations can wait, as they measure challenges that come after that initial adoption moment. In a way, it’s a measure of whether would-be users believe that the initial feature set and vision are compelling ways to solve our problem, and whether they believe the problem is even worth solving. The Success Quotient captures all of these dynamics at once. (To be sure, some products make massive leaps forward merely by updating their positioning, their messaging, or their offer, and those are worthy causes, just not the focus of this article.)

What thresholds demonstrate success?

It’s easy to find companies bragging about how many users they earned when they first launched on Product Hunt or similar places, but it’s quite difficult to find publicly referenceable examples of what the actual ratios looked like, since they are frequently not launching just with their target users. I’ll do my best to share some public examples, and then I’ll need to ask for your trust based on what I have seen. Suffice it to say, the companies that post big numbers on first release are at the top of the spectrum I’m about to describe, so if you have a multi-thousand-user first day, or a giant waitlist for your B2B or enterprise product, you’re in a great, strong position. The question is what to do or think below those ranges.

For example:

Instagram acquired 25,000 users in one day upon launching in October 2010. It had 100,000 downloads by the end of the first week, and 1 million by mid-December.1

Slack earned 8,000 requests on its first day and 15,000 by its second week, and it grew at a rate of 5% to 10% every week for the first year.2

GitHub earned 6,000 beta signups when it launched in April 2008.3

And of course, the one to shame them all, ChatGPT from OpenAI won over 1 million users in its first week, 57 million by the end of its first month, and 100 million not long after.4

Again, each of these examples does not tell us the ratio, but at some level, if the absolute uptake number is in the thousands, you’re probably doing just fine. Here is how I think about each of the thresholds across each of the business contexts

To make these numbers come to life, this means, for example, that if you pitch 10 prospects who have the stated pain your product solves for your enterprise product, and if only one or two of them are asking for follow-up, you’re probably not yet on the money. Whereas if you can get three or four of them to move forward, this is workable and you likely can build a business. The bottom two categories are both amazing places to be, and now you simply need to live up to the hype of your own offering.

These are not concrete numbers, and this is not meant to be a scientific measure. It is possible to win starting from lower than these thresholds, and I’ve also seen companies that have never pitched their product because word of mouth grew them through the first few stages. This is startupland, and anything is possible, but it’s also important to know how close you are so you can decide how to fix the problems when they exist.

My numbers are dangerously low—now what?

First, you’re in incredibly strong company. You are not a failure (unless you ignore the next steps). No one writes about this, but it is in fact the most common place to be by volume of shots on goal. This is controversial advice, but my suggestion is to try a new solution, a new problem statement, an adjusted market, or some combination of these.

The conventional wisdom is to spend more time iterating on the existing solution. I’m a huge fan of iterative software development, with customers deeply in the loop; however, that is the best plan only after you establish a strong anchor starting point. It’s not impossible (just very unlikely) to iterate your way from the danger territory into the higher uptake rates, but where I believe most founders and product people go wrong in these situations is moving straight to iteration, which incentivizes thinking small. To get from dangerous territory into “strong to quite strong,” you need to move big levers (see my post on data-driven vs. savant-driven first insights).

A great example is how Twitch was founded. The initial traction for Justin.tv, a streaming service that followed the founder around 24/7 and allowed people to upload any content, was not seeing the strong uptake required for sustained growth. Instead of trying to make a progressively better feed of Justin or make it easier to upload more types of content, the team paid attention to the value users were deriving from the product and identified that gamers didn’t have an easy way to livestream their gameplay. This was a big shift, and one large enough that Justin.tv made the transition to Twitch, which we now know as a household name.

When I say iteration isn’t the key to solving this particular problem, I don’t mean that you should stop talking to users! Quite the contrary, in fact—talking to them is the best way to derive these big insights that you need to unstick your sticky anchor. It may be that you need to solve a different problem, or solve the problem with a superior solution or for a different market. Or, if you have nearly unlimited capital and time, you can definitely try to iterate past your sticky anchor; just don’t expect that process to yield fruit on a timeline of weeks or even months—expect it to take years.

Remember that the path to a successful product is rarely a straight line. Embrace the journey of discovery, pivot when necessary, and stay committed to solving real problems for your target audience, as this resilience and adaptability are what truly differentiate successful ventures in the long run.

Hi! If you enjoyed these insights, please subscribe, and if you are interested in product coaching or fractional product support for your venture, please visit our website at First Principles, where we help the most ambitious founders make a difference.

https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/102615/story-instagram-rise-1-photo0sharing-app.asp

https://www.businessofapps.com/data/slack-statistics/#:~:text=After%20a%20year%20of%20privately,15%2C000%20by%20the%20second%20week.

https://earlyusergrowth.com/startups/#github

https://blog.invgate.com/chatgpt-statistics#chat-gpt-users